Who at Cloudflare planned this LAN party?

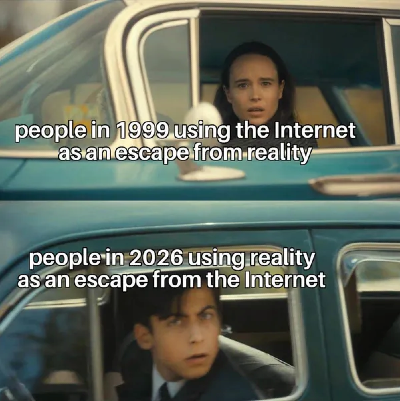

Welcome to Good Computer (commonly confused with Bad Computer iykyk). This is a blog where I'll be writing about all things tech and culture that I'm lightly and intensely following, whether it be about piracy, infrastructure and video games or AI, hating to remember things and not escaping the internet. Probably some writing on phone culture as well, obviously. Enjoy, Willem.

A LAN party done today could be seen as many things. A romantic gesture to a lost era of compute; cord-gore vs cord porn IRL; a dinner party; a digital virus hot bed; a test of planned obsolescence compatibility; a place to build a local internet. And, obviously, a place to play video games together.

But, for the past year or two now, I keep coming back to LAN parties because of their ability to get a diverse group of voices to build, deliberate and play with digital infrastructure. Over 8+ hours we can bring our personal devices, disable firewalls(!), build a local network and harness our screen-time energy by playing with and thinking collectively about how the internet used to work, how it works now, and maybe how we might want it to work in the future: both big internet and small internet.

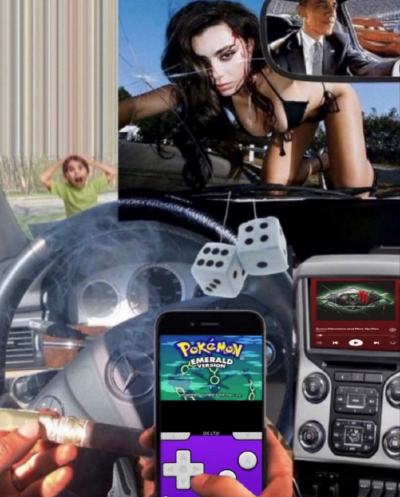

In the 90s computer networks came with a radically different set of values and architecture. It was characterised by dial up internet where people were using anonymous usernames, scrolling forums and message boards. The internet, just before the dot-com bubble began, was seen as the classic NEW FRONTIER outside of government control, shown amazingly in the, now hilarious, classic A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. The new entrepreneurs of the California Ideology were just starting to begin to understand how they could capture a market of users that could generate real capital, later leading to the temporary failure of this capture with the bust of the dot-com bubble. These experiences were built on networks of dial-up connections that came with distinctive sounds of modems handshaking that any Gen X or boomer would comment on, connected through your telephone cable port and running at 56 kilobytes per second. An image like the one below would take about 10 minutes to download at that speed.

These slow speeds, along with the popularity of multiplayer PC games of the 90s like Doom, Quake, Starcraft and Age of Empires, created a moment between the late 90s and 2000s where people would build local networks to play video games together. PCs packed up in cars, friends and friends of friends who head to someone's basement or garage to connect over a local area network and game together. Even though broadband was becoming popular by the early 2000s, video games, especially graphically demanding games, had mainly been designed at the time for local play or experienced too many latency issues to play over the internet. It was in these spaces that we saw the last real moments of people gathering to build their own networks for play. Pulling cables around dining room chairs and fold-out tables to play games together. This was a form of collective making that faded as broadband became ubiquitous and games simply shipped with multiplayer protocols baked in.

“For artists raised on LAN parties and lag, boss fights and battle passes, it’s only natural that video games show up in the studio—not just as references, but as frameworks.”

from the exhibition statement for lfg (2023) at THEHOLE, New York.

The past few years have witnessed LAN party aesthetics resurface across academic and art contexts. Whether it be a forced friction of computing through slow, poetic, non-human, small or anti-ambient compute or similar qualities that reflect a nostalgia around gaming and the utopic era of networks in contemporary culture. A romanticism of the aesthetics of old technology like cables, cables, and more cables; crt, nintendo 3ds (Janne Schimmel) and even plasma displays; gamer-core technology like Monster; literally LAN parties themselves. There's something powerful in the nostalgia driven by 90s / 2000s tech optimism, or the veneer of it, of this seemingly last era of “compute” right as the internet was becoming hyper commercialised. MTV was in its prime, music videos had incredible budgets and, well, subcultures still overtly meant something? Maybe it was that they had harder lines and borders between them. I remember LIL INTERNET in an episode of NEW MODELS mentioning how when the internet became more popular, people could just look up how to dress like a certain subculture, fashion being a gateway for sensing relatability and access. This searching for subcultural aesthetic codes became a way of appropriating access, rendering subcultures less gate kept, less distinct, and consequently less valuable to those within them. No wonder people want to access some kind of vibe that was from the 90s and 2000s: culture was exciting and valuable, and the LAN party is a picture of this mood.

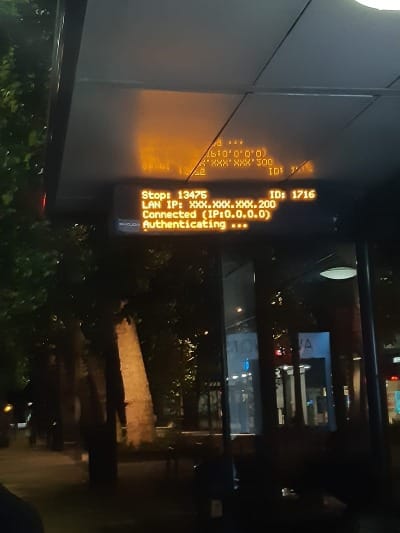

Now, in 2026, gamers play almost exclusively online, from a home desktop on voice chat, clicking from their $5k aesthetic set up. The internet is seamless (most of the time, as you'll see below). Gaming has optimised itself around bandwidth, response times, battle royals, in-game purchases and concerts. And when FPS winners are sometimes determined by their internet speed, or latency, why would you want the internet any other way? Performance demands invisibility, and the best infrastructure is the one you never notice.

In 2025 alone, the internet saw two major infrastructure outages that produced a fantastic amount of memes. Namely the AWS crash in October 2025 and Cloudflare's in the following November. There were other outages along the way, but these were the ones that affected enough people to start discourse moving online. The best image coming out of this was the one of the water purifier not having access to being online. No internet, no purified water.

I did have a clean transition from coffee maker to academic-speak, which felt ridiculously Claude-coded, so let’s just go here: the sentiment around these crashes, the feeling of total loss of control and understanding of the systems that govern us (the internet's back end), is what academics like Spencer Jordan and Peter Boxall call a crisis of subjectivity. Basically, the feeling of being captured by a network of power (like 2008-era capitalism or maybe 2024/5-era AWS(?)) that you didn't choose and can't easily exit. In this state, we’ve fallen into a collective inarticulacy, where we have more technology embedded in our lives than any generation in history, yet we lack the actual vocabulary to describe how these networks are trapping us or even how they function (see Tim Morton's hyper-object). This could be the result of living in a phantasmagoric digitally, a kind of ghostly condition where the internet feels like a weightless dream that deliberately hides the concrete reality of the server and cables from our daily view. But when the cloud breaks, the stutter could create a productive "interruption of the digital’s illusion of perfection" that suddenly forces the hidden infrastructure into our awareness (language we see a lot in the art world. See Trevor Paglan).

Jordan, among others, is talking about a post-...-post-modern(modem) (see PostPostPost) condition where we are moving past the irony of the early 2000s, the flexible non-answer of post-modernism, and towards a pragmatics of trust. This is the active decision to stop being an observer and move towards being a reconstructor. To proactively build something and be reliable even while knowing the system is flawed (we don't understand the system we're in, the values in the system are relative, etc. etc.). We’re looking for a connection we can actually feel, choosing the physical friction of a copper cable over the haunted, depthless experience of a centralised web.

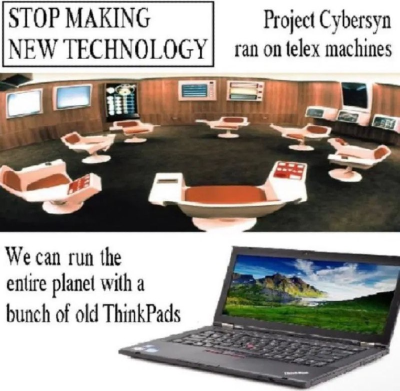

After doing some reading on the Cloudflare outage for this post, one thing was clear: it's wrong to think that these things wouldn't happen if there were simply more data centres. There need to be more people, orgs or companies that assemble the infrastructure of the internet, along with understanding not only where the centres sit, but also who runs and governs them. Also, a certain level of care and tending to the networks, as opposed to the infinite techno-accelerationism that Adressen would be asking for. Cloudflare's last outage, described in their post-mortem report, was a software problem: a configuration file in their Bot Management system that grew too large and crashed. It wouldn't have been solved by having more data centres built in rural towns, or even in downtown London, causing issues for communities being displaced, noisy cooling systems, and the gentrification that follows these tech campuses into neighbourhoods. Not that Brick Lane isn't gentrified already. The problem was centralisation: one company's bug took down X, ChatGPT, and Spotify for hours.

But there's already a lot going on, and has been going on, around networks and ways of combating this. There's NYC Mesh: a volunteer-run organisation of decentralised wi-fi nodes stretching across three boroughs that stayed online during Hurricane Sandy. Guifi.net in Catalonia has over 37,000 active nodes built by rural communities that telecom companies just decided weren't worth serving. And on the software/socials side of things, there's Mastodon and the fediverse, 2.8 million people across 9,500 independently run servers talking to each other without needing Zuckerberg in the middle of it. This is infrastructure people are using right now. And I'll even say there were some interesting crypto projects on physical decentralised networks... However, of course, they lost tenability after the last cycle and token devaluation.

I feel like the question here is not about building necessarily, but about subtracting and caring for infrastructure rather than adding. There’s a strong desire to build and produce technology, while we should first be broadening the scope of who understands these systems and what they could be used for to build for equitable internets. And for that to happen we also need people who can translate between concepts of infrastructure and digital sovereignty to people who might struggle connecting the dots. I think that's where a LAN party can act as a place for beginners to advanced network thinkers to experiment through play, interrogate and test out new systems and the affordances of them. It's a quick launch from theory to practice, and being able to expose people to these ideas.

At a LAN party you show up, plug in, and troubleshoot why your laptop won't connect to the switch. Someone needs to manually assign IP addresses or set up DHCP; there's an argument about whether to run the server on someone's mac or an old ThinkPad someone brought. You need to ping someone beside you to see if the basic command of connecting is actually happening, and troubleshooting begins when it doesn't. You run up against compatibility issues, old pcs and new macs not cooperating, and some people wanting to play one game over another. The network issues aren't abstract anymore. They're why you can't join a match or connect to one of the dedicated local servers with the install files. Here we get to see the cycle of friction at play, fixing the systems that you can then immediately benefit from through play, that produces an effect which no Substack article can really do: the act of understanding through poetic experience.

This starting point of the LAN party seems like a beginning point for network workshops to create a dialectical, non-didactic way for people to become translators between the network engineers and the users. Not all of us need to understand the internet fully; there just need to be more people who can experiment in the middle and understand both sides. We don't need everyone to know how a country's power grid affects the scaling of internet infrastructure, but we do need more people to have unique infrastructure literacy because these decisions now affect human rights, national security, blackout risk, and democratic governance, not just tech policy.

"One unexpected outcome of this shift is the resurgence of analogue and tactile media not as nostalgia, but as infrastructure for meaning, trust and identity."

Reset to Real, Victória Oliveira

LAN party aesthetics are showing up not just in art contexts but across cultural production, manifesting in the 2020s in ways that resist reduction to nostalgia alone. They're showing up now in ways that feel different from pure nostalgia: whether it be commercialisation of esports in huge local rooms or fashion shows using them as afterparties. Most of us know of the analog return like vinyl sales, film cameras and wired connections. and it's been a while now that 2000s aesthetics have been popular for younger people, and it just keeps pushing. There's streaming fatigue as people realise they're paying for five subscriptions and still can't find anything to watch. Offline/local-first movements producing products like Quarry are building tools that work without the cloud, giving us opportunities to explore network sovereignty. Things are tangible, local, and weird. It makes me wonder whether these values—particularly among younger generations—might cultivate more people who position themselves as translators between infrastructure and user or at least develop some literacy around how systems work. Hopefully we'll continue to see more people curious about the tangible bits of the web, how it works, and the politics about it.

"Just as much as the internet is superficial apps and interfaces, the internet is built upon low level networking protocols and programming languages. Even deeper, it consists of wires, servers, and data centers. These pieces of infrastructure that sit underneath the browser can't be ignored when attempting reform. They are not easy things to change or remake."

What Happened to the New Internet? by Bryan Lehrer

Thankfully, this kind of experimentation and exploration around internet infrastructure isn't anything new. Academics, writers, experimenters—lots of people coming out of the 2010s Are.na cohort—and those before us have been trying to sort out ways of de-platforming and decentralising all kinds of internet spaces. Lots of work done, lots falling flat, some holding up. Bryan Lehrer makes a really great comment at the end of his blog post about the New Internet, a bit of a canon I'm touching on here and his journey working in these spaces, where he mentions how it's the hard powers and the strict internet infrastructure that was born out of the telegram cables of Britain's colonialist periods that we're fighting against when trying to create new platforms and new spaces online. Power is necessarily translated through material conditions, and the internet with its infrastructure is definitely material (as of writing, Iran has been in an internet blackout for 25 days). It's going to be hard to try to generate new spaces that are rethinking this hard power. And I'm not pretending I have any sort of answer lmao. However, what I do know through my work with UKAI Projects, running workshops and creating art, is that conversations and exploring these questions with others are important. Dialectic and non-didactic forms of intervention are needed in any kind of space to be criticised. And the LAN party is 100% down to create a dialectic about internet infrastructure.